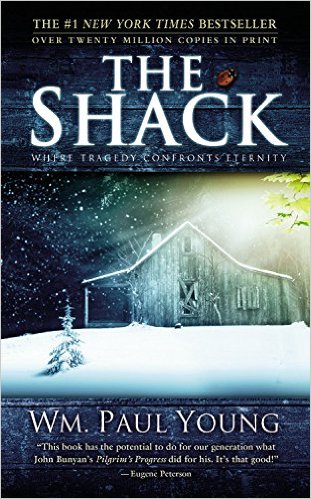

The Shack has taken America by storm, and like most storms it has kicked up a good bit of controversial dust along the way. I recently reviewed it in order to get a free copy.

The Shack has taken America by storm, and like most storms it has kicked up a good bit of controversial dust along the way. I recently reviewed it in order to get a free copy.

Mackenzie Alan Phillips is the central character in The Shack. His young daughter, Missy, was murdered by a serial killer, and over the years the resulting Great Sadness has almost incapacitated him. He’s a Christian. A seminary graduate, in fact. But while his wife seems to have been able to find comfort in God, “Mack” has not yet been able to forgive God for letting Missy be murdered.

So God meets Mack at the Shack, the place where Missy died. Only God is not one but three: “Papa,” a jovial black woman; Jesus, a large-nosed Jewish carpenter; and “Sarayu,” a colorful apparition in the basic shape of an Asian woman. Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Papa explains to Mack that he has taken the shape that will bring the most comfort to Mack. Papa, Jesus, and Sarayu lead Mack through various experiences and conversations which free him to forgive his daughter’s killer and restore his love for God.

Several good things can be said about this book: It pictures the deep mutual love among the persons of the Trinity, and it stresses man’s need to live dependent on God.

Hmm. That was fast. But I meant it.

However, a few significant problems exist, too:

- Putting words in God’s mouth is a dangerous thing.

- God tells Mack, “I don’t need to punish people for sin. Sin is it’s own punishment, devouring you from the inside. It’s not my purpose to punish it; it’s my joy to cure it.” (120)

- The book despises hierarchy—both among the godhead and among humans. Jesus tells Mack that the persons of the Trinity are submitted to one another in the same way they are submitted to Mack.

- Papa sometimes speaks irreverently or even slightly scatalogically.

- The reason given for God representing himself in Scripture as male is said to be that good fathering would be far more lacking on earth than good mothering, and God wanted to pick up the slack.

- The book has a barely disguised disdain for religion (and seminary education!). The church has little or no place in the book.

- Sarayu suggests that it’s not a “fatal” mistake to view Eden as a myth. (134)

- Jesus leaves it a bit unclear as to how He regards world religions. (182)

- To borrow explicitly from John Piper (who gets it, as usual, from Jonathan Edwards): God’s love for man is seen in His making much of man rather than freeing man to make much of God. (190)

- God is awfully soft on sin. Papa says, “I don’t do…guilt or condemnation.” (223) Mack’s sinful heart is a wild wonderful mess rather than an object of divine wrath.

Perhaps the most significant problem in the book is the way that it deals with the most significant problem in Christian theology, the problem of evil. Man’s choice is sacrosanct in The Shack. Over and over—ad nauseam—God insists He will not violate man’s choice. But this leads the god of The Shack to say exactly the opposite of what the God of Scripture has said. Papa explains, “I did not purpose Missy’s death, but that doesn’t mean I can’t use it for good.” (222) This is striking because it so closely matches—and explicitly contradicts—what Joseph told his brothers in Genesis 50:20, “You planned this for evil, but God planned it for good.” Another phrase in the book is quite similar. Papa tells Mack, “Just because I work incredible good out of unspeakable tragedies doesn’t mean I orchestrate the tragedies.” (185) But God said through the prophet Amos, “Does disaster come to a city, unless the Lord has done it?” Absolving God of responsibility for evil by making him purposefully impotent to stop it—shackled by the inviolability of man’s self-determining choice—is not the Bible’s way.

The book is meant to be a comfort to hurting people who cannot accept God’s love. But Mack’s question toward the beginning of the book stands unanswered: “I just can’t imagine any final outcome that would justify all this.” (127)

The Bible does offer comfort to hurting people, but that comfort extends from the powerful hands of a God who “does according to his will among the host of heaven and among the inhabitants of the earth.” These words come from the most powerful world ruler of his day, Nebuchadnezzar (Daniel 4:35). And he continues: “None can stay” those powerful hands or even say to God, “What have you done?” Far from being opposed to hierarchy, Jesus said, “All authority on heaven and in earth is given to me” (Mt 28:19). His benevolent rule will bring all human history to a final outcome which will justify all the pain of human existence.

For a more lengthy scriptural case for this view, check out this excellent article or this excellent book.