I come to the Trinitarian Bible Society’s two–part, 38,000-word “Examination of the New King James Version,” written by Albert Hembd, with a question. The question is precise and direct: Will the author ever mention a specific passage in which the NKJV translators made a better choice than did the KJV translators? I am writing this paragraph before reading anything Albert Hembd has ever written; I’ve never even heard of him before writing these words—and he’s got a lot of space in which to say something positive about the NKJV. But, based on what I know of the Trinitarian Bible Society for whom he writes, I’m guessing—with sadness—that the answer to my question will be no. Hembd will not find a single specific translation choice made by the NKJV translators that he views as superior to the corresponding choice in the KJV, not even superior based on the narrow issue of language change—that is, a place where the NKJV replaces an archaic word with a contemporary equivalent.

Now I suppose it is possible that the NKJV translators failed completely in the 800,000 choices they made while revising the KJV (there are about 800,000 words in the KJV, and the NKJV translators had to make a choice regarding every one of them: keep or revise?). Educated people can do foolish things, even repeatedly. But is it really likely in this case? Is it likely that these particular highly qualified men, evangelical men with PhDs who’ve spent years studying and teaching the Bible, men who have written biblical commentaries, men who happen to have one undeniable advantage over the KJV translators when translating for a contemporary audience—namely that they speak contemporary English—failed to make a single improvement upon the KJV?

Will the author ever mention a specific passage in which the NKJV translators made a better choice than did the KJV translators?

[Reading…]

The answer is yes. I have to admit that my guess proved inaccurate. Hembd did have specific praise for the NKJV.

Once.

I have now read Hembd’s long critique of the NKJV—and all of TBS’ other critiques of the NKJV, for good measure, and I found just one verse where they offered praise for specific translation choices in the NKJV. That’s a total of maybe 45,000 words, all of which are negative except for one paragraph—a paragraph which occurs on the 78th page of Hembd’s 90-page piece.

This is why I respect Chuck Surrett, longtime Academic Dean of Ambassador Baptist College—and why I earlier wrote an article focused on his work. He’s the only leader in the Received Text world that I know of who was willing 1) to look at a large number of examples in the NKJV (in other words, to produce a sufficient sample size) and 2) to give the NKJV the nod on a number of occasions when he felt it made a superior choice.

Surrett’s conclusion wasn’t quite so measured: he ends up calling the NKJV “decidedly inferior” to the KJV (even after acknowledging—by his criteria—that 44% of choices he checked in NKJV Romans were superior to the KJV). But I can really respect someone’s conclusion when he manifests the charity and reasonableness Surrett showed—and that Paul commanded:

Let your reasonableness be known to everyone. (Phil 4:5 ESV)

I’ve been thinking a lot about this verse in the last year. The KJV has Paul commanding “moderation” here, but I think this is what I call a “false friend”—a misleading mismatch between Elizabethan and contemporary Englishes. “Moderation” had a now obsolete sense of “clemency” that eventually became our “avoidance of extremes.”

And the Greek word here in Phil 4:5 (ἐπιεικὲς; epiekes) doesn’t mean (what we mean today by) “moderation”: it doesn’t mean avoidance of extremes. It means “not insisting on every right of letter of law or custom: yielding, gentle, kind, courteous, tolerant” (BDAG). Other translations go with “gentleness” (NKJV) or “forbearance” (NKJV margin) or “graciousness” (CSB). The word also shows up in Titus 3:2, which urges elders “to speak evil of no one, to avoid quarreling, to be gentle, and to show perfect courtesy toward all people.” One commentator suggested “meeting people halfway” as a good gloss.

And that’s one thing that even the gracious Chuck Surrett hesitates to do in his comparison of the KJV and NKJV, and that Hembd does only once (more on this later). Neither allows the KJV and NKJV to meet halfway. They don’t acknowledge toss-ups, passages in which the right translation isn’t fully clear—or in which there are multiple acceptable English renderings. I see almost no evidence in their writings that there can be toss-ups; there has to be Certainty of the Words, not only in text but in translation.

But “in the judgment of the judicious,” to borrow a phrase from the KJV translators’ preface, there are toss-ups in English Bible translation. They’re almost always minor; we’re not talking about passages in which Christ’s deity is take it or leave it. They’re minor—but they’re everywhere. People who are demonstrating their gracious and gentle reasonableness to all men are able to say the kinds of things master Hebrew Bible translator Robert Alter says:

The practice of translation…entails an endless series of compromises, some of them happy, some painful and not quite right because the translator has been unable to find an adequate English equivalent for what is happening—often brilliantly—in the original language.… Translation often involves painful compromise—you gain something through the loss of something else.

I have never heard this note from my brothers who promote the KJV and TR. But I ought to, if they’re reading the KJV cover to cover, because there’s someone else I respect who thought this way: the KJV translators.

As…variety of translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures: so diversity of signification and sense in the margin, where the text is not so clear, must needs do good, yea, is necessary, as we are persuaded. We know that Sixtus Quintus expressly forbiddeth that any variety of readings of their [Catholic Latin] Vulga[te] edition should be put in the margin (which though it be not altogether the same thing to that we have in hand, yet it looketh that way), but we think he hath not all of his own side his favourers for this conceit. They that are wise had rather have their judgements at liberty in differences of readings than to be captivated to one, when it may be the other.

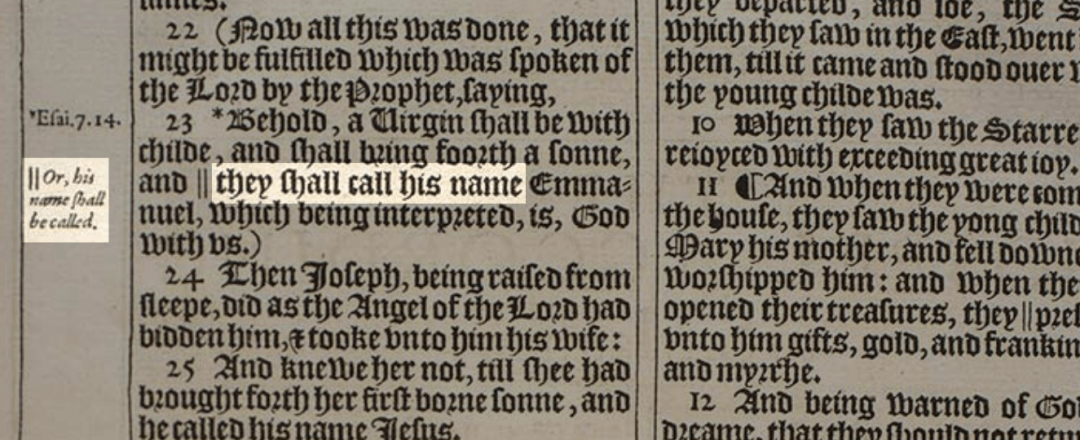

The KJV translators were true to their word, and they included translation options in the margins of the 1611 KJV. It was minor stuff, usually, but they felt for the reasons they just gave that it was worth their effort to include:

By contrast, and back to the main topic, Albert Hembd’s examination of the NKJV turns up one toss-up. And his overall conclusion is absolute, brooking no compromise:

[The NKJV] seriously diluted and obscured important doctrines of the Scriptures in key verses.… We must…state firmly that we do not deem [the NKJV] a faithful translation. Indeed, we cannot recommend it at all.

Textual criticism

Hembd’s major criticism of the NKJV is not actually that it’s a bad translation, nor that it uses the wrong textual basis (it uses the same textual basis as the KJV), but that it includes footnotes mentioning variant readings in the critical and Majority texts of the New Testament. Hembd’s entire first article—19,000 words—is about text, not translation, even though (I’ll mention this important fact again) the NKJV is based on the same Hebrew and Greek texts as the KJV. He also strays back to this topic multiple times in his second piece. I am unwilling to engage this topic with him—though I’ll have one agreement to express with him about it much later—and will focus instead on his arguments against the NKJV’s translation choices.1

“Translational errors of a major doctrinal impact”

Early on, Hembd comes close to a positive word about the NKJV in these two lines:

Relatively speaking, the New King James Version is better than the other modern versions because its actual text is not based on the modern critical Greek text.…

The New King James translators made many unnecessary translational changes and mostly for the worse.

In that first line’s acknowledgment and in that second line’s “mostly” I found a little hope that I might find Hembd meeting the NKJV translators halfway in a few places. Perhaps he might acknowledge that some portions of the KJV are, due to changes in English over the last few centuries, difficult for contemporary readers—and the NKJV was, therefore, an improvement in those narrow instances. I would think that might be acceptable for my brother, Albert Hembd. It avoids blaming the KJV translators for something beyond their control, namely the evolution of English. Besom becomes broom (Isa 14:23); conversation becomes conduct (1 Tim 4:12)—good? Or perhaps Hembd might notice places where the NKJV took advantage of the advances in Hebrew and Greek scholarship that have occurred in the last century or so—unicorn becomes wild ox (Num 23:22)?

Alas, it was not to be. Except for that one verse I mentioned, Hembd finds only flaws in his examination of the NKJV.

I’d like to work through the 20 specific passages he brings up. I’ll spend more time on the 10 he thought were truly serious. I won’t try the reader’s patience with long discussions of the others.

My case: The Trinitarian Bible Society and other brothers who prefer the Textus Receptus tradition of Greek New Testament editions ought to welcome the NKJV: it is based on the same Greek and Hebrew texts as the KJV, it uses language intelligible to today’s English speakers, and its choices are reasonable (Phil 4:5) even when they differ from those made by the KJV translators.

1. “Hell” (KJV) vs. “Hades” (NKJV)

The first example Hembd gives of “translational errors of a major doctrinal impact” is a word that occurs 11 times in the NKJV: “Hades.” In each of those places, the KJV has “hell” instead.

He calls this “a very grave, but also intentional, translational problem.” (Emphasis original: I have retained his original emphasis in all quotes.)

And Hembd believes he knows the intention behind the change:

The Greek word hades, as employed in classical mythology, does not at all mean a place of eternal punishment and estrangement from God. To the contrary, it primarily means ‘the abode of the dead’, and therefore, figuratively, ‘the grave’. In this sense, if one were to fail to take into account the New Testament’s use of the word as a whole, the word could be mistaken to mean ‘a condition in which a person is taken out of existence’, hence, annihilationism.…

One could wonder whether the use of the word hades were employed so as to give annihilationists—those who deny the eternal damnation of the wicked in hell for ever—opportunity for foisting their views on unsuspecting readers. Annihilationists say that the wicked will simply be destroyed out of existence at the Judgment Seat of Christ. Of course, this is a serious error.

Bible translators—outside the NET Bible, which has translation notes—don’t usually get a chance to explain their reasoning behind individual translation choices. All you get is their text. This moist, dark area of ignorance has become a fruitful place for mold-like conspiracy theories to grow.

What you end up with is this very common trope in literature promoting the exclusive use of the KJV and/or TR:

- Argue that a given rendering in a modern version could easily be read to support doctrinal error [even though that error is contradicted elsewhere in the new translation].

- Omit to use available sources to determine what most likely motivated the modern translators [despite Proverbs 18:13].

- Posit that the modern translators were in fact motivated by a malign desire to soften, undermine, or even destroy sound doctrine [even though the translators may give every outward sign of being conservative Christian brothers].

- Fail to present an example of someone who has been moved into the given error by the use of said modern version [the NKJV has been out for 40 years; surely it would have happened by now].

Now back to discussing hell/Hades… Hembd does ask a fair question when it comes to “hell” vs. “hades,” he truly does:

The translators of the New King James affirmed that it was their intention to provide a mere language update of the Authorised Version, so as supposedly to make the Scriptures easier for the modern English reader to understand. Why then change a word which is already easy for the English speaker to understand? Who does not know what hell is? Why introduce a new term with which many may not be familiar?

But with all charity—I can’t find any evidence that Hembd wants an answer to his own question. He doesn’t go looking for one in any commentaries used or even written by men on the NKJV committee. He doesn’t check any of the standard dictionaries, such as NIDNTTE or TDNT or EDNT. None of the standard lexicons—except for BDB, cited once—such as BDAG or Louw-Nida appear in his footnotes (he does also cite the older Thayer lexicon once). The NKJV translators’ views are given no representation, only (highly negative and suspicious and lengthy) interpretation.

For example, he reaches for a transparent guilt-by-association argument in his discussion of hell/Hades. He says that the first English Bible to opt for “hades” instead of “hell” was the 1881 English Revised Version—and, he says,

We can only be alarmed. The heterodoxy of several members of that translation committee, notably William Robertson Smith, a Scottish higher critic, and George Vance Smith, a Unitarian, is all too well known.

Hembd does acknowledge that he isn’t aware that any of the NKJV translators lean personally toward annihilationism, as Smith and Smith did. But then he suggests that perhaps the NKJV translators made this error “unconsciously.” This is as much grace as Hembd will give his brothers in Christ, the NKJV translators: their “serious” and “intentional” doctrinal deviations may perhaps have been committed without their active knowledge.

Or, he says, maybe they were influenced by the “nefarious” (his word) New American Standard Bible. This is a very bad thing, in Hembd’s view, though he doesn’t explain why in his piece. He argues that “the high number of times where the NKJV departs from the Authorised Version and adopts the same or very nearly the same reading as the NASB betrays their sympathy for and intellectual alignment with the philosophy and methodologies of the NASB translators.” The methodology of the NASB is generally considered to be to translate “as literal as possible,” which is precisely what Hembd elsewhere says he likes about the KJV, so I’m still left unsure as to what dangerous methodology he’s referring to.… He appears to assume that his editors and his audience will find agreement with the NASB to be a reason to reject the NKJV.

Hembd might have mentioned that pretty well all the major modern evangelical English Bible translations use “Hades,” including the ESV, CSB, and NIV. Every significant collection of living evangelical biblical scholars who has been asked to translate the Greek word hades into English has chosen the transliteration “Hades” rather than the translation “hell.” Are they all unconscious annihilationists?

I did some of the homework I expected Hembd to demonstrate (at least in footnotes), and I came up with two points in defense of the choice “Hades” in the various passages at issue.

First, if we are to distinguish Gehenna (Matt 5:22, etc.) and Tartarus (2 Pet 2:4 only) from Hades, it’s helpful not to render them all with the same English word, as the KJV does (with hell). I’m fine with the KJV translators’ choice; I’m also fine with the choice of the NKJV translators. If it were up to me, I’d probably go the way the HCSB did, however, because there’s something satisfying about consistency: in it, hades is always translated “Hades”; gehenna, “hell” or “hellfire”; and tartarao, “Tartarus.” People are going to have to do some study no matter what to understand all this. I don’t think any of the major evangelical English translations (including the KJV and NKJV) got any of these words “wrong,” much less that they will mislead people into doctrinal error. There was plenty of doctrinal error out there when all we basically had was the KJV. The heretics on the ERV committee didn’t grow up on the ERV, after all.

Second, doesn’t every one of Hembd’s critiques of the NKJV’s choice of the English word Hades apply to the Holy Spirit’s choice of the Greek word ᾅδης (hades)? Surely, if using the English word Hades risks people thinking of the Greek underworld instead of the biblical hell, weren’t ancient Greek people who actually believed in that underworld more likely to be confused by that word choice than modern people whose fuzzy knowledge of Hades comes mainly from the Disney movie Hercules? Perhaps if Hades was good enough for Jesus, it should be good enough for us. Reality is that people will always misunderstand if they want to: it is impossible to translate in such a way that guarantees that no one will misunderstand. But long documents like the Bible are able to say enough to minimize the likelihood that a sincere reader will be misled. The Bible defines Hades through its comments about the afterlife, comments that read the same in the NKJV as they do in the KJV.

On his first example—which Hembd actually views as sufficient by itself to jettison the entire NKJV (“Seeing then that the NKJV has abandoned this standard, we cannot recommend this translation. Indeed, the New King James is foundationally deficient in blurring this essentially important truth”)—I find myself unpersuaded. No major doctrinal impact; just several options which judicious, “reasonable” people (Phil 4:5) could choose.

2. “Experience” (KJV) vs. “character” (NKJV) in Rom 5:4

The second NKJV error with “major doctrinal impact” that Hembd selects is in Rom 5:4. Hembd argues strenuously that “experience” is far superior to “character” as a rendering of δοκιμή (dokime) here. I’ll quote 5:3–5 here for context:

KJV: We glory in tribulations…: knowing that tribulation worketh patience; And patience, experience; and experience, hope: And hope maketh not ashamed; because the love of God is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Ghost which is given unto us.

NKJV: We…glory in tribulations, knowing that tribulation produces perseverance; and perseverance, character; and character, hope. Now hope does not disappoint, because the love of God has been poured out in our hearts by the Holy Spirit who was given to us.

And, as with “Hades,” Hembd lines up against every major modern evangelical English translation of Scripture. Not only the NKJV but the ESV, NASB, NIV, CSB, and others all choose “character.” Why is Hembd so alarmed? What doctrine is at stake here? He says,

The word…experience speaks of…experimental religion. However, the New King James makes a very major change in this one word and in doing so, the doctrine.

“Experimental” is itself a false friend for some readers. Today it means almost the opposite of what it used to mean: it means something “untested.” Readers of 19th century and older evangelicals (such as the Puritans) will know this word’s older sense, however. And it still does show up in some contemporary English dictionaries (NOAD). Look at the last line, the archaic sense:

I think Hembd’s idea is that “character” focuses on outward behavior (?) whereas “experience” focuses on true heart religion. I had a little trouble grasping how it is that the NKJV changes the doctrine being taught here, because Hembd never explains what he thinks “character” means. But I hope I’m understanding him accurately.

Whatever his idea, it leads him pretty deep into his suspicions of the NKJV translators:

We cannot but feel that the failure to note the experimental component of this verse by the NKJV translators reflects the general dearth of experimental religion in our day. This is indeed a day in which mere historical, non-saving faith in the head (but not in the heart) is often taken by many to be actual, vital godliness in the soul; and even the godly of our day, we fear, have been lulled by the general lukewarmness of our time to a deadness in spiritual matters. Accordingly, we cannot but regard the New King James Version as a fruit of this spiritually barren age. There is a deficiency, it seems to us, in the NKJV’s setting forth fundamental experimental truths of the Word of God. Does this deficiency perhaps stem from a relative unfamiliarity of the translators themselves…with experimental matters when compared with Christians of the past?

That’s a lot to discern from one word choice—a choice that nearly all contemporary evangelical translations make. Are nearly all living evangelical translators questioning the importance of heart religion by choosing the word “character” here?

In reality, Hembd is being tripped up by a “false friend.” It took us till example 2 for this to occur. (One of the reasons I read pieces like Hembd’s is that they find false friends for me that I haven’t found yet—they can be tough to spot, even for trained eyes.) “Experience” in a context like this didn’t mean in 1611 what it means today. The KJV translators had a different sense that is not available to us.

Follow my logic.

Hembd is correct to say that “dokime properly means proof arising from having survived a test or trial.” And, quite interestingly, there’s an obsolete sense of “experience” that fits dokime—and this context—perfectly. Here’s the Oxford English Dictionary, the only dictionary that reliably records obsolete senses of English words:

But note that the OED says that this sense passed into sense 3:

Sense 3 is our current sense of the word, the one that Hembd assumes is what the KJV translators meant. The ideas of trial and proof, of practical demonstration, have fallen out of the word over time.

Hembd says, “What is so hard to understand about the word ‘experience?’” And if we were talking about a contemporary text, he’d be right. But we’re not. The KJV is a 400-year-old text—and if it is indeed 86% Tyndale in the New Testament, it’s in many places a 500-year-old text. And in this passage there is nothing in the context—in part because “experience” occurs in a list—to tip off an English reader that “experience” once had a sense we now lack.

Our word “character” today isn’t perhaps quite as good as the KJV translators’ word “experience” was in 1611. But the sense of “experience” that we need is no longer available to us. BDAG says dokime means “the experience of going through a test with special reference to the result,” and it offers these glosses: standing a test, character.”

“Character” is the best single English word we have to translate dokime—though I think the two-word solution in the NASB (which Hembd also criticizes) shows careful attention to nuance and is probably the best overall choice in contemporary English: “proven character” (the CSB opts for the same).

The KJV translators didn’t make a mistake; modern readers aren’t dumb for not knowing the subtle changes that have happened to the word “experience” over the last four centuries. And modern translators aren’t wrong to choose a different word.

There is no major doctrinal impact in the NKJV’s choice here; it is simply reflecting changes in English over time. “Reasonable” people might reasonably differ on the very best way to translate this word into today’s English.

3. “Narrow” (KJV) vs. “difficult” (NKJV) in Matt 7:14

The third major NKJV error Hembd alleges comes in the Sermon on the Mount. In Hembd’s view, this error strikes to the heart of the gospel itself:

In mistranslating this verse the New King James has cast doubts on the doctrine of salvation by grace through faith in Christ alone! We cannot but chide with the New King James translators on this critical point and point out their serious deficiency in rendering fundamental doctrines of the Gospel.

And what is the NKJV translators’ serious, gospel-denying error? See if you can figure it out before you read his explanation.

KJV: Strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.

NKJV: Narrow is the gate and difficult is the way which leads to life, and there are few who find it.

I couldn’t guess what the theological error was. But here’s what Hembd said:

By mistranslating the Greek word as difficult, the New King James would give the reader the impression that the poor sinner must work his way to God, that salvation is somehow a work of his own willpower with a little of God’s assistance helping him to overcome the heart of evil within. But no, salvation is all of grace; it is not of works, but of faith, and that faith is all God’s work (see Ephesians 2.8). Salvation is narrow because it is alone by Christ by grace through faith.… It is a narrow way because it is an exclusive way.

That’s a lot to discern from one word choice—a choice that many contemporary evangelical translations make. Are the NKJV translators (and the ESV, CSB, NET, NLT translators) denying salvation by grace through faith? Are they trying to insert works righteousness into the New Testament?

No.

Let’s talk this through.

The Greek word here, θλίβω (thlibo), is actually not an adjective but a participle: a verb. It means “to cause something to be constricted or narrow, press together, compress, make narrow” (BDAG).

“Narrow” is a good choice, then. The KJV translators did well. But that’s also the most natural contemporary English gloss for the different Greek word at the beginning of the verse, στενός (stenos). The KJV translators had “strait” available to them; we don’t. NOAD says that the adjectival use of strait is “archaic,” not obsolete—but I’ve been Englishing for almost four decades now, and I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone use it. Plow boys certainly don’t know it. It isn’t truly available.

Modern translators tend to use “narrow,” then, for stenos—and it ain’t good English to use the same word twice (they can’t say “the gate is narrow and the way is narrow”). So what can they do with thlibo?

Several modern English translations opt for “constricted.” I like that option. Others render stenos with “small,” leaving “narrow” open to use for thlibo. That’s another good solution.

But there’s another option entirely, one worthy of Hembd’s consideration. I did some poking around in commentaries, and several—Carson (EBC), Nolland (NIGTC), and France (NICNT)—helped me see that thlibo has more than just the literal sense of “compressing, narrowing.” It also has a metaphorical sense, “oppressing, afflicting.” Here it is in 2 Thessalonians 1:6:

God considers it just to repay with affliction those who afflict you.

This is actually the sense of thlibo (and of its noun form thlipsis) that predominates in the New Testament. In this context, “hard” or “difficult” would be the way to reflect this sense.

The metaphor Jesus is using could definitely be pointing toward the more literal sense. The KJV translator’s choice of “narrow” was reasonable and good. But that’s not the only option.

Hembd says that the NKJV is forcing Jesus into a contradiction by having him say that the way is “difficult” or “hard” that leads to life, because elsewhere he says that his “yoke is easy” and his “burden is light” (Matt 11:30). But it is surely not a contradiction, anymore than it was a contradiction for Paul to later say that “through many tribulations we must enter the kingdom of God” (Acts 14:22 ESV). In fact, that is quite possibly—according to the NKJV and other translators—what Jesus was saying here: through many afflictions we must enter the kingdom.

Why bother switching to another interpretation when “narrow” works just fine? That is a valid question. I think that in a literal translation like the NKJV that was supposed to be sticking to the KJV as much as possible, I would have used “narrow” for stenos and tried something like “constricted” for thlibo. The parallel to thlibo in the previous verse is a “broad” or “spacious” road; the ESV goes with “easy” there, presumably to match their (reasonable) interpretation of thlibo. But I don’t see that meaning attested in the lexical citations.

On balance, I think Hembd is right to prefer not to use the metaphorical extension of thlibo here—but he is certainly wrong to find a denial of the gospel in a translation choice that has such good reasons behind it. As some wise men once said, “They that are wise had rather have their judgements at liberty in differences of readings than to be captivated to one, when it may be the other.” That’s why I like having access to multiple translations in my Bible study—so I can spot little differences of nuance and explore them.

There is no major doctrinal impact from the NKJV’s revision here; just a few options that judicious, “reasonable” people (Phil 4:5) could choose.

4. “His” (KJV) vs. “their/its” (NKJV) in Zech 9:17

Hembd charges the NKJV translators with major malpractice in Zechariah 9:17:

We now look at a text which the New King James translators deliberately chose to alter, purposely revising what is said in the original language.

Understanding Hembd’s point will require us to look at the surrounding context.

Here’s the KJV:

And the LORD their God shall save them in that day

as the flock of his people:

for they shall be as the stones of a crown,

lifted up as an ensign upon his land.

For how great is his goodness,

and how great is his beauty!

Corn shall make the young men cheerful,

and new wine the maids.

Here’s an earlier edition of the NKJV:

The Lord their God will save them in that day,

As the flock of His people.

For they shall be like the jewels of a crown,

Lifted like a banner over His land—

For how great is their goodness

And how great their beauty!

Grain shall make the young men thrive,

And new wine the young women.

The most recent edition of the NKJV has “its” in place of “their” in both places above, and footnotes that say, “Literally, his.”

What’s going on here?

Hembd believes he knows. He not only notes the NKJV translators’ error but professes to know the malign motivations behind it:

The NKJV translators opted deliberately to change the pronoun…so as to give glory to man instead of to God! Such a rendering of the text is not only wrong, it borders on heresy. It would say that the Lord saves worthy sinners, He saves those who are good!… We cannot but view this mistranslation as an obscuring of the doctrines of free grace and of the doctrine which is itself set forth by the passage.

Hembd concludes:

In all, we cannot but feel that the NKJV translators are shaky in their doctrinal moorings in important fundamentals of Law and Gospel.

That’s a lot to discern out of one word choice.

Why, indeed, the profusion of options here—“his,” “their,” and “its”?

My first step in answering a question like this is to take a vote. See what the evangelical (and other) translators do. They’re divided. The ESV and MEV stick with the KJV (so does the mainline Protestant CEB); the NASB, CSB, NIV, and NLT do what the NKJV translators did.

The NKJV translators said that they “have not pursued a goal of innovation” (NKJV preface). “They have perceived the Holy Bible, New King James Version, as a continuation of the labors of the earlier translators.” That isn’t a promise to change nothing, but it might have been a good idea to side with the KJV when possible.

Commentators I checked thought it was indeed possible. Here’s a standard evangelical commentary by Klein in the NAC set:

In the final analysis the text allows for either view: that the pronoun refers back to the gemstones in v. 16, or either to the Messiah or the Lord. But the antecedent of Hebrew pronouns typically occurs in the immediately preceding context. Lacking certainty, the best approach to the question locates the antecedents in v. 16, the gemstones. Further, it is not unusual for a third person masculine singular pronoun to represent a plural antecedent. The NIV translation reproduces this approach well.

And that’s the answer: God inspired the text to be ambiguous. The context leans heavily toward the NKJV (read it and see), but the grammatical forms lean toward the KJV. Both leans lean hard, but neither is determinative. We can’t have perfect certainty here. It’s okay—no, it’s good—for careful students to be aware of both options. That’s what footnotes are for, and the NKJV provides one.

I can force myself to see why Hembd thinks the NKJV is attacking salvation by grace here. Someone could possibly read the NKJV as saying that God “will save them” because their goodness and beauty are so great. But verb tenses in the prophets are often difficult. I find it unlikely that anyone who’s read his whole Bible will conclude that Ephesians 2:8–9 is the obscure passage and this the clear. Does Hembd know of a single NKJV reader who has come to the interpretation he takes of the NKJV wording? He doesn’t say.

There is no major doctrinal impact here; just various options (his, His, its, their), all of which judicious, “reasonable” people (Phil 4:5) could choose.

5. “Worshiping” (KJV) vs. “kneeling” (NKJV) in Matt 20:20

Hembd’s fifth criticism of an NKJV translation choice comes in Mathew 20.

KJV: Then came to him the mother of Zebedee’s children with her sons, worshipping him, and desiring a certain thing of him.

NKJV: Then the mother of Zebedee’s sons came to Him with her sons, kneeling down and asking something from Him.

Hembd argues,

In the Authorised Version, every occurrence of the Greek word προσκυνεω (proskuneo) is translated the same, namely, as worship. Even in the New King James, most of the time it is translated thus. Indeed, the NKJV renders proskuneo as worship in Acts 10.25, where Cornelius falls down to worship Peter. Yet here it has failed to translate the word properly when dealing with a far more important Person than Peter, One Who is indeed worthy of worship.

Hembd acknowledges,

We cannot say, on the mere ground of this one verse alone, that the editors of the New King James did not believe that Christ, as God, is worthy of worship.

But, he observes,

We must say that there is a certain carelessness and indifference toward the significance and importance of this doctrine as it is clearly set forth in this verse. We cannot but think the NKJV translators’ failure to render proskuneo in its true meaning of worship in this verse reveals a lack of reverence.

Why did the NKJV translators choose “kneel” instead of “worship”?

Proskuneo literally (or etymologically, rather) means “kiss toward”; it is “frequently used to designate the custom of prostrating oneself before persons and kissing their feet or the hem of their garment, the ground, etc.” (BDAG). This sense logically gives rise to its more common sense in the NT: “worship.” There are many times when the context clearly indicates that “worshiping” and not “prostrating” is in view:

You shall worship the Lord your God, and him only shall you serve. (Matt 4:10)

But look at the use of this word in Matthew 18:26:

The servant fell on his knees [proskuneo], imploring him, “Have patience with me, and I will pay you everything.” (ESV)

The KJV does an admirable job upholding the principle of lexical concordance here (using the same English word for the same Hebrew/Greek word where possible) by sticking with “worship.” But if both “worship” and “prostrate” are available senses, doesn’t the context favor the latter? Was the servant according some kind of divine status to his master? Maybe. Reasonable people could differ.

And look at the use of the same word in Mark 15:19:

[The soldiers] were striking his head with a reed and spitting on him and kneeling down in homage to him. (ESV)

“Homage” is translating proskuneo. It’s not that using “worship” would be wrong here; it’s quite clear that the soldiers’ “worship” was sarcastic. The ESV translators were understandably uncomfortable, however, with saying that the wicked soldiers mocking Jesus were “worshiping” him. So they opted for a different word.

That appears to me to be what the NKJV translators were doing in Matthew 20:20. They weren’t denying or weakening Jesus’ deity; they were opting—as the Greek word allows—to leave some more doubt about the purity of the mother’s motives, given the greedy and selfish nature of her request. (The physical description of the setting—with the mother “coming” to Jesus—also leans me toward thinking that the more physical, literal sense of the word is being meant.)

Whether this one ancient woman intended to give worship or mere homage in no way detracts from the worship Christ is due. And, to be clear, I’m fine with the KJV translators’ choice of “worship” here. I see the options as a toss-up, with “kneeling” tossed slightly higher up than “worshiping” (for the reasons I’ve given). But English readers who have both options can hit their lexicons and commentaries with a useful and interesting question: what was the motivation of this woman? I’m not disappointed, then, that the English translations don’t all agree in their rendering of the word proskuneo in this verse.

There is no major doctrinal impact in the choice of “kneel” or “worship”; just viable options, both of which judicious, “reasonable” people (Phil 4:5) could choose.

6. Marginal Notes on 1 John 5:7

The sixth “translational error of a major doctrinal impact” is not a translational error. Here Hembd strays back to textual criticism, complaining about the marginal notes at 1 John 5:7. I am unwilling to engage this topic with him and will continue to discuss the NKJV’s translation choices.

7. “Took on him the seed of Abraham” (KJV) vs. “does give aid to the seed of Abraham” (NKJV) in Heb 2:16

KJV: For verily he took not on him the nature of angels; but he took on him the seed of Abraham.

NKJV: For indeed He does not give aid to angels, but He does give aid to the seed of Abraham.

Hembd views the NKJV’s choice as very serious:

The NKJV alters with its translation a very important passage in Hebrews 2.16 concerning Christ’s incarnation and His taking our human nature.

He acknowledges that other statements in the NKJV in this chapter affirm Christ’s incarnation, but he thinks that

the NKJV’s rendering of this verse in this way weakens its testimony to this all-important, fundamental doctrine, thus weakening Scripture’s testimony to the incarnation of the Saviour.

In fact, the NKJV affirms the incarnation multiple times in this paragraph—and it does footnote the option Hembd prefers.

Hembd has once again lined up against nearly every major modern English Bible translation in existence. And he fails completely to give any reasons why his brothers in Christ have made this choice. He might have checked Ellingworth’s standard commentary on Hebrews in the NIGTC, which came out 15 years before Hembd’s article. Ellingworth explains that the KJV and NKJV renderings both have a long history, and he presents a careful discussion citing four reasons for siding with the NKJV (and all other modern English translations). Among them: the writer to the Hebrews switches to the present tense for this verse, which the KJV translators had to alter to past in order for their interpretation to make sense. And note the italics in the KJV: they also had to supply a very significant word—“nature”—in order for their interpretation to work. I refer readers to Ellingworth for more details.

Hembd appears to me to be right that “help” is a strained meaning for the key Greek verb here. BDAG seems a little unconvinced. The verse is difficult. I like O’Brien’s suggestion in his PNTC volume, following John A.L. Lee (in a superb book on NT lexicography that I really loved) that the word should still be translated “take hold of.” Christ, in other words, doesn’t seize angels and take them to heaven; he seizes humans. But that interpretation has its difficulties, too—and the translations, I admit, all implicitly reject it!

I don’t see any major doctrinal impact here: the whole paragraph soundly affirms the incarnation, no matter what good translation you look at. What I see are various options that judicious, “reasonable” people (Phil 4:5) could choose.

8. “Appearance” (KJV) vs. “form” (NKJV) in 1 Thess 5:22

Hembd’s next example of a “translational error of a major doctrinal impact” has an interesting history in my work. I originally made it the last in a list of 25 “false friends” in my book. But then John McWhorter brought up this example in my interview with him, and that got me thinking about it again—and digging into the OED again. Here it is:

KJV: Abstain from all appearance of evil.

NKJV: Abstain from every form of evil.

My initial thought, suggested to me by a friend just as I drew my writing of Authorized to a close, was that I was dealing with sense 7 in the OED:

So I wrote in my first edition—and told John McWhorter—that appearance in 1 Thess 5:22 in 1611 English meant “instantiation of.” I later realized that I should have kept reading in my OED. Here’s the very next sense, and look at one of the citations it gives!

I’m not honestly sure, at this moment, which sense the translators KJV intended to use. I tend to defer to the amazing lexicographers at the OED, whoever they were: the word meant “semblance.” So in the second printing of my book I replaced this example. The KJV translators seem to have intended to convey here that we shouldn’t even do things that look evil but aren’t—like, I don’t know, visiting a casino just to use the restroom?

That is, indeed, a stronger stricture than what is found in the NKJV. It’s why my family didn’t go to movie theaters when I was a kid.

Interestingly, the very Greek lexicon Hembd cites (by the 19th century lexicographer Joseph Thayer) gives both “appearance” and “form” as potential translations for the word. The sole reason Hembd gives for preferring “appearance” over “form” is—and I confess I had to read between the lines in a rather brief discussion—that the former is stronger. But that’s not the way Bible interpretation ought to work: find the stiffest and most demanding interpretation of every passage and stick with it. And later in his article, Hembd himself argues that the NKJV is wrong because he believes its rendering is too harsh (see no. 20 below)! (The NKJV pipes for Hembd, and he does not dance…)

So what did Paul mean? All of the major modern translations (except the MEV) go with “form” or “kind.” Gordon Fee (NICNT) explicitly rejects the KJV’s rendering here and gives reasons. He agrees with Calvin in seeing “abstain from every form of evil” as continuing Paul’s brief discussion of prophecies: Test them all; keep the good ones; toss the bad ones (see vv. 20–22). It is generally indeed best to read statements as connected to surrounding ones if possible instead of as wholly separate. And here it’s surely possible.

I like what Wanamaker (NIGTC) does: he says that Paul is sticking with the contextual flow here. But he’s broadening in this final phrase of the paragraph from prophecies to all forms of evil. Test all prophecies; keep the good ones; abstain from the evil ones—along with every kind of evil out there.

I could not find any judicious or reasonable people who agree with Hembd’s interpretation of this verse; I couldn’t find any commentators at all who adopted it. This is one thing that inclines me to think that the KJV translators didn’t mean what Hembd thinks they meant. But I don’t know for sure. Reasonable (Phil 4:5) people might differ.

9. Marginal notes on Acts 8:37

The sixth “translational error of a major doctrinal impact” is not a translational error. Here Hembd strays back to textual criticism for the second time in a list of ten. Here he objects to the marginal notes at Acts 8:37. I am unwilling to engage this topic with him and will continue to discuss the NKJV’s translation choices.

10. “The king’s daughter is all glorious within” (KJV) vs. “The king’s daughter is all glorious within the palace” (NKJV) in Ps 45:13

Each time Hembd brought up a passage in which the NKJV committed a “translational error of a major doctrinal impact,” I tried to figure out what it was just by looking.

This is one where I was stumped.

KJV: The king’s daughter is all glorious within: Her clothing is of wrought gold.

NKJV The royal daughter is all glorious within the palace; \

Her clothing is woven with gold.

I guessed that Hembd was concerned about “glorious within” (KJV) vs. “glorious within the palace.” But I wasn’t sure.

But Hembd is sure. The NKJV’s error here, in his mind, “has grave doctrinal consequences.” The royal daughter in this case is actually the king’s bride, the church, Hembd says. By affirming that she is “glorious within,” the Psalm (Hembd says) is affirming what 2 Cor 5:17 does, that Christ makes his bride into a new creation, giving his bride an inner beauty (1 Pet 3:3–4).

Hembd would have benefited from doing a simple word search, however (and from noticing that the translations are once again generally against him). The word translated “within” here never means “within a person’s spiritual being.” It always refers to buildings: people entering “within” them or Solomon overlaying the temple “within” with pure gold.

I think that’s what the KJV translators meant, too—though they were perhaps being artfully ambiguous here, allowing for either interpretation. And maybe that’s a wise course. But it certainly isn’t obligatory.

There is no major doctrinal impact here; just various options all of which judicious, “reasonable” people (Phil 4:5) could choose.

“Translation problems of lesser doctrinal impact”

I’ve talked in some detail through Hembd’s ten major objections to NKJV translation choices—well, eight, because he chose to dedicate two of them to textual issues. It’s not as if reasonable people can differ over every last proposed translation of every passage in Scripture; it’s not as if there are an infinite number of “good” translations of every passage. But there are often more than one.

We’ll see the same as we turn to the next ten passages Hembd lists.

Hembd now turns to

examine passages where we judge the NKJV’s errors to be of lesser doctrinal significance, but where it does indeed incorrectly render the sense of the passage. Surely this is important! The true child of God desires to understand all of Scripture that he can. If like Job he esteems the Word of God more than his necessary food (Job 23.12), how much then should he desire a translation of the Scriptures that is as accurate as possible!

I agree! But as I said in the introduction, I will not try readers’ patience with long discussions in the following ten passages. I’ll just offer my quick takes.

11. “Quick understanding” (KJV) vs. “delight” (NKJV) in Isa 11:3

KJV: And shall make him of quick understanding in the fear of the LORD: And he shall not judge after the sight of his eyes, Neither reprove after the hearing of his ears:

NKJV: His delight is in the fear of the LORD, And He shall not judge by the sight of His eyes, Nor decide by the hearing of His ears;

I don’t know what “quick understanding” means. And every major translation goes with the NKJV here. The Hebrew is very difficult: the literal sense of the word here is to “smell.” Every translator is stuck interpreting this rather than translating it; if it’s a metaphor, it’s obscure. “Reasonable” people (Phil 4:5) could rightly differ here.

12. “Imaginations” (KJV) vs. “arguments” (NKJV) in 2 Cor 10:5

KJV: Casting down imaginations, and every high thing that exalteth itself against the knowledge of God, and bringing into captivity every thought to the obedience of Christ;

NKJV: casting down arguments and every high thing that exalts itself against the knowledge of God, bringing every thought into captivity to the obedience of Christ,

“Imaginations” doesn’t make good sense to me, shaped as I am by our English and not Elizabeth’s. Looking at this, I began to suspect that we might be dealing with a false friend. Indeed, I think Hembd has been tripped up by another one. See the last line of the OED’s sense 2:

“Imaginations” is parallel to “thoughts” in 2 Cor 10:5 in the KJV. I think the KJV translators did just fine—and they footnoted “reasonings”:

But we today don’t mean “thoughts” when we say “imaginations.” We mean flights of fancy; the creation of internal pictures that aren’t real.

The Greek word is more like “reasonings,” as Hembd acknowledges. “Arguments” is, then, better for today’s English speakers. Only the MEV sticks with “imaginations.” All major modern translations choose something else.

13. “Affection” (KJV) vs. “mind” (NKJV) in Col 3:2

KJV: Set your affection on things above, not on things on the earth.

NKJV: Set your mind on things above, not on things on the earth.

All translations today side with the NKJV here. The word can shade over into the affective domain (see Phil 3:19, for example); but it is primarily cognitive. Then again, I don’t see much of a difference between “Set your mind…” and “Set your affection.…” To set one is to set the other.

14. “You” (KJV) vs. “you” (NKJV) in Isa 7:14

KJV: Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign; Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, And shall call his name Immanuel.

NKJV: Therefore the Lord Himself will give you a sign: Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a Son, and shall call His name Immanuel.

See discussion below at 15.

15. “You” (KJV) vs. “You” (NKJV) in Luke 22.31–32

KJV: And the Lord said, Simon, Simon, behold, Satan hath desired to have you, that he may sift you as wheat: But I have prayed for thee, that thy faith fail not: and when thou art converted, strengthen thy brethren.

NKJV: And the Lord said, “Simon, Simon! Indeed, Satan has asked for you, that he may sift you as wheat. But I have prayed for you, that your faith should not fail; and when you have returned to Me, strengthen your brethren.”

Hembd says,

It is very important that the English reader of the Scriptures have in his hands a version that differentiates between the singular and plural of the second person pronouns. We have only listed a few of the verses where this is critical.

Hembd is right that modern English does not distinguish as KJV English did between singular and plural in second person pronouns. This is a genuine loss for English Bible translators, because both Hebrew and Greek did make that distinction. But Hembd’s complaint is with English, not with the NKJV. I think a better solution would be to use modern pronouns and give footnotes at the relatively few places where English pronouns’ divergence from Greek may cause a misunderstanding. A Bible translator friend of mine said his organization has a list of about fifteen such passages.

I weigh the pros and cons of thee/ye vs. modern second-person pronouns in Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible; so far I’ve received no answer to any of my arguments there. No language can perfectly match the forms of Hebrew or Greek. English, for example, has no grammatical gender—and that’s a loss no one complains about, despite the fact that 1) Old English once had it and 2) it is occasionally helpful for interpretation (for example, in determining the referent of a pronoun). Also, neither KJV English nor contemporary English distinguishes number among relative pronouns (who, whom)—and no one complains. Vikings swept into English and learned it as adults, smoothing off Old English’s complicated edges in the process. This is just what happens in language, and we can’t and shouldn’t turn back the clock. How in the world, for example, could we add back in grammatical gender? Translation between languages therefore always involves tiny little compromises.

16. “he” (KJV) vs. “He” (NKJV) in Psalm 37:23

KJV: The steps of a good man are ordered by the LORD: And he delighteth in his way.

NKJV: The steps of a good man are ordered by the LORD, And He delights in his way.

I tend to agree with Hembd here: I’m generally opposed to the capitalization of deity pronouns, in part because of passages like this where translators get forced to choose an interpretation because of their overall capitalization policy. I don’t mind the NASB being a “Bible code” Bible that includes special “shortcodes” like this for those in the know—or like capping OT quotations, for example. But the NKJV isn’t a good place for this custom.

And yet surely every one of the many Christians who still capitalizes deity pronouns faithfully in their writing thinks they are doing honor to God. And they are. This custom may have been ill-conceived; it may have outlived its usefulness; it may confuse more readers than it helps; it certainly has cons and not just pros. But people had good motivations for establishing it, and they have good ones for using it. Can’t we say the same about the NKJV translators? They had God-honoring reasons for choosing to use this convention in their Bible translation. And once they made that choice, they were forced into other choices like this one. It’s unfortunate, but not a “translation error.”

17. “The spirit…lusteth to envy” (KJV) vs. “The Spirit…yearns jealously” (NKJV) in James 4:5

KJV: Do ye think that the scripture saith in vain, The spirit that dwelleth in us lusteth to envy?

NKJV: Or do you think that the Scripture says in vain, “The Spirit who dwells in us yearns jealously”?

Hembd accurately poses the question here:

Does the Greek word for ‘spirit’…refer to the Holy Spirit, as the New King James has rendered it? Or could it instead refer to the regenerate nature of the born-again man which also lusts for righteousness, in accordance with John 3.6, which tells us ‘that which is born of the Spirit is spirit’?

The earliest Greek manuscripts did not distinguish between uppercase and lowercase letters. But sometimes receptor languages simply don’t allow ambiguity in the same way Hebrew and Greek did. English, for example, demands the capitalization of proper nouns. So English does not allow neutrality: it’s either spirit or Spirit. The KJV translators chose one option; the NKJV translators chose another. Hembd advances no exegetical arguments in favor of the KJV’s choice; he leans instead on praising the KJV translators’ “cautio[n].” But they’re not being cautious; they’re making a choice, just like every other translator. Hembd provides a few interpretive options for this passage in his brief discussion, but he doesn’t do what a Bible scholar is supposed to do: he doesn’t give us the current state of the question. Why do some modern translations (NASB, HCSB, ESV) go with the NKJV here, and some (NIV, CSB, NLT) go with the other? There must be reasons, and there are—reasons Hembd doesn’t mention and yet that, clearly, empirically, “reasonable” (Phil 4:5) people differ over.

18. “he” (KJV) vs. “He” (NKJV) in 2 Thessalonians 2:7

KJV: For the mystery of iniquity doth already work: only he who now letteth will let, until he be taken out of the way.

NKJV: For the mystery of lawlessness is already at work; only He who now restrains will do so until He is taken out of the way.

When I got to this eighteenth “translational problem” in the NKJV, I was, frankly, shocked—in a very good way. We’ve arrived at the one exception to Hembd’s avalanche of criticism against the NKJV. Here at no. 18 Hembd suddenly did four things he doesn’t do anywhere else in his lengthy piece.

- He praised the NKJV for being more literal in one word choice than the KJV (iniquity vs. lawlessness).

- He praised the NKJV for being more readable for modern audiences in another word choice (letteth vs. restrains).

- He gave a balanced discussion of various interpretive options, followed by a judicious but somewhat tentative and deferential decision to side with the KJV.

- Then he gave credit to the NKJV translators for providing the option he prefers in a footnote.

I felt like I was suddenly reading a different article. See for yourself:

The New King James here has rendered the word for iniquity somewhat more literally, which can be good, having rendered it ‘lawlessness’ which indeed is what the Greek word says. It has also translated the word ‘let’, which formerly meant ‘to hinder’, as ‘restrain’, which is more easily understood by modern readers.

Excellent! He was actually a bit more critical of the KJV translators than I would have been (I think iniquity was a fine choice in 1611). But clearly, let is misleading to modern readers—it’s a false friend, and one that actually now means the opposite of what the KJV translators intended.

And here’s his judicious conclusion:

Not capitalising the personal pronoun leaves the passage open for interpretation. It leaves it open as to whether the restrainer is the Holy Spirit or some other power. To its credit, the New King James (at least in the 1982 edition) appends a footnote in which it acknowledges that the pronoun could be in lower case.

Again (see no. 16), I agree that capitalizing deity pronouns has weightier cons than pros; but once that choice is made in general, it requires the translators to make interpretive choices in specific passages. So the problem, again, is with the editorial policy—one that had a good motivation behind it—and not so much with its implementation in any given passage.

But what just happened? Why the switch from maximum skepticism to graciousness? I don’t know. But let me give credit: Hembd did well here, both in substance and in tone.

19. “He” (KJV) vs. “they” (NKJV) in Isaiah 53:9

KJV: And he made his grave with the wicked, And with the rich in his death; Because he had done no violence, Neither was any deceit in his mouth.

NKJV: And they made His grave with the wicked— But with the rich at His death, Because He had done no violence, Nor was any deceit in His mouth.

Hembd says:

Once again, the New King James seems to have come somewhat under the nefarious influence of the New American Standard…. and in doing so has robbed the church of an important truth.

What truth?

The sovereign Christ decreed to lay down His life; no one, not even the Father, could take it away from Him if He were unwilling.

What’s going on here? First, I note that if the NKJV translators wished to undermine the truth that no one could take Jesus’ life but instead he laid it down of his own accord, then why did they “change” this one word and leave John 10:18? “No one takes it from Me, but I lay it down of Myself. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it again.”

Second, a check of the standard commentaries reveals that this could be a textual issue: the Great Isaiah Scroll, the chief treasure of the Dead Sea Scrolls, has the plural rather than the singular here. Given that the NKJV translators, led in the OT by James Price, specifically said they were not using a text different from that of the KJV translators, it is more charitable to say what Oswalt did in his commentary on Isaiah:

1QIsa has wytnw, 3rd masc. pl., a more normal way of expressing the virtual passive (“they have assigned” = “it was assigned”). But 3rd masc. sg. (as per MT) can be used in this way also (GKC, §144d). (NICOT)

In other words, Gesenius’ grammar allows for the singular form to be a virtual passive here. This is very arcane, scholarly, nerdy stuff; but Oswalt is the standard evangelical commentary on Isaiah, and Hembd (whose Hebrew training appears to exceed my own?) should at least have briefly reported his reasoning.

20. “Heretick” (KJV) vs. “divisive” (NKJV) in Titus 3:10

KJV: A man that is an heretick after the first and second admonition reject;

NKJV: Reject a divisive man after the first and second admonition,

There is genuine appeal in using the English cognate heretic, because the Greek word is αἱρετικὸν (hairetikon) is the etymological source of our word heretic.

But our word heretic has taken on a very specific meaning that it arguably didn’t have in Paul’s day. Today heretic means, “a person believing in or practicing religious heresy,” or “a person who differs in opinion from established religious dogma.” In Paul’s day the related Greek word could mean something more general: “pertaining to causing divisions, factious, division-making” (BDAG). The same root shows up elsewhere in the NT speaking of the “party” or “sect” [αἵρεσις, hairesis] of the Pharisees or Sadducees. Paul even uses the word more or less positively (or at least neutrally) in Acts 26:5: “After the most straitest sect of our religion I lived a Pharisee.” Indeed, the KJV itself translates this word as “sect” about half the time.

It is possible that Paul meant the specific heretic here and not the more general divisive man. The Theological Dictionary of the New Testament goes that direction; it thinks the word was a technical term (i.e., heretic) from the first, even in the NT. But other authorities go a different direction, including the NKJV translators; and given that we have only one NT occurrence of this particular noun to go on, I lean pretty strongly toward the NKJV (other English Bible translators are with them overwhelmingly).

Nonetheless, seeing both options is valuable. Neither one has to be the winner when we all have easy access to both. Hembd “confidently affirm[s] that the modern interpreters are wrong,” but God chose to use a word whose meaning is not exhaustively certain. The KJV translators themselves say in their justly famous preface that this is precisely the reason why they offered alternate translations in the margins. “Reasonable” (Phil 4:5) people can differ over the best way to translate this word.

Readability difficulties in the KJV

I’ve run into several brothers in the wild wild web who have tried to list for me difficult and archaic words in the NKJV (or other modern translations). The point they’re trying to make is that those of us who object to the readability of the KJV by the contemporary plow boy are using a double standard. We’re fine with archaic and difficult words in the NKJV, they say; why not in the KJV?

I’ve seen this kind of thing repeatedly over the years, and every time I see it my mouth hangs open. Can any KJV defender possibly wish for me to compare numbers of archaic or difficult words in the KJV vs. a modern translation—when KJV defenders themselves, including the Trinitarian Bible Society, put out lists of hundreds of dead words and false friends in the KJV? No such books exist for any of the modern translations. Why? Because they’re not needed.

One of the logical fallacies they taught me in English class long ago was “insufficient sampling.” I don’t deny that, in a few cases, the words chosen by a given modern translation are more difficult to contemporary readers than those chosen by the KJV translators. This happens because modern translations’ goal is not just to make everything easier; it’s also to be accurate. And sometimes modern translators pick what they believe to be a more accurate translation that is, nonetheless harder than the word chosen by the KJV translators: “the sun was up” (KJV, Jdg 8:13) is indeed easier to understand than “ascent of Heres” (NKJV and many other translations). But the latter is more accurate (check commentaries for why). I also don’t deny that modern translations include difficult words (mandrakes, Sheol); any faithful Bible translation will, because the Bible includes difficult words and concepts.

But, overall, there’s no comparison in reading ease between the KJV and any major modern English translation. The KJV was translated into an English we simply don’t speak anymore; and it’s no slight against the KJV to say this, or Hembd himself would have been wrong to mention that “restrains” in 2 Thess 2:7 is easier for modern readers than “letteth”.

So I thought of something: I bet I can find examples of words that are noticeably easier in the NKJV than in the KJV just from the twenty verses Hembd selected for analysis. And in half the verses, I did:

- Matt 7:14 – strait (which NOAD marks as “archaic”) vs. narrow

- Zech 9:17 – corn (a false friend) vs. grain

- Matt 20:20 – desiring (which the OED marks as archaic) vs. asking

- 1 John 5:7 – bear record (still hanging on by a thread in contemporary English, but decidedly uncommon according to the NOW Corpus) vs. bear witness

- Heb 2:16 – verily (not a very hard word, but surely a dead one) vs. indeed

- Ps 45:13 – wrought vs. woven

- Isa 11:3 – after vs. by

- Luke 22.31–32 – desired (see no. 3 above) vs. asked

- 2 Thessalonians 2:7 – letteth vs. restrains

- Titus 3:10 – the KJV’s syntax places “reject” last instead of first, like the NKJV and other translations, all of which are following the expectations of modern English.

Now, in half the KJV verses Hembd lists I did not find significant readability difficulties. And even in the ten above I’m not saying all these difficulties are insurmountable for all readers (though some are for many readers, like corn instead of grain). But they are difficulties: they’re at least little speed bumps on the road—and every one of them is unnecessary. A switch to modern English words and word order is simple in each case. Surely, a fair examination of the NKJV should mention the advantages of contemporary English for today’s plow boys more than once.

What Hembd gets right

As we draw closer to a conclusion, I think it is only fair that my own “examination” of Hembd’s work find some positives. What does Albert Hembd get right in his piece?

Bad marketing

I think he proved that the marketers of the NKJV should not have claimed to be doing a mere update to the KJV, an update necessitated by language change. I have not personally seen them claim this, but I wasn’t paying attention to Bible advertisements in the 1980s and 90s, and I take Hembd’s word for it. In places like Matthew 7:14, Zech 9:17, and James 4:5, the NKJV translators could and should—given those marketing claims—opt for the same interpretation the KJV translators used. They probably could and should have stuck with “worship” in Matthew 18 and 20, too.

Or they—and I’m not sure whether this is the marketers’ fault or the translators’ fault—should simply not have claimed to be doing a minimalist revision of the KJV. By opting for different interpretations in these places, they took an unnecessary risk.

Hembd could have made this limited point instead of the far-reaching one he tried to make, and he would certainly have won the day. Given the readiness of his audience (the TBS constituency) to stick with the KJV, he wouldn’t even have needed to draw a conclusion alleging dishonesty or perfidy among the people behind the NKJV. He could merely have raised the question: Is this translation consistent with its marketing materials?

He vs he

I won’t belabor this one; I’ll only repeat that I agree with Hembd: capitalizing deity pronouns is a bad idea in a Bible translation (and almost everywhere else!). It forces unnecessary interpretive decisions.

Thee and ye

Hembd is also right that the older second-person plural form, thee and ye and so on, are more transparent to the original Greek than are the contemporary English forms of those pronouns. I’ve offered some countervailing arguments above, but he is still fundamentally right on this point.

The danger of textual notes

I did not discuss above in any detail Hembd’s complaints about the textual-critical footnotes in the NKJV. But I think he is also right—although this is something of a self-fulfilling prophecy—that those many marginal notes dedicated to textual variants are more alarming than useful for the Bible-reading public. I think there should have been fewer such notes. Probably far fewer.

(Hembd didn’t mention this, but it still supports his viewpoint: I think it fundamentally odd that Majority Text notes were included at all, though I can see why Hodges and Farstad would have done it, given their production of a Majority Text GNT. There is some edifying utility in having Nestle-Aland/UBS Text readings in the margins of the NKJV: many Christians have been using critical text Bibles for decades, and it’s useful to know in a small group session why my fellow church member’s Bible doesn’t read exactly the same way mine does in 1 Thess 4:1. But there are no major New Testament translations based on the Majority Text. There doesn’t seem to be an edifying reason to include them. It’s an arcane point useful mainly to scholars: namely, it shows that Scrivener’s TR doesn’t always follow the Majority. That is a point that just doesn’t need to be made—let alone over and over again—in the margins of a layperson’s Bible. That discussion belongs elsewhere.)

Some discussion of textual variants is appropriate and even needed in the margins of English Bible translations. The KJV translators thought so. They included at least eleven textual-critical notes. That might be too few, honestly, especially now that we know more about the manuscript history of the New Testament. But the NKJV translators—I have to step over to Hembd’s side here—included too many. Empirically speaking, they have alarmed some people.

What I learned from this exercise

Now, what did I learn from this lengthy exercise?

I found more false friends

For one, I found a few more false friends in the KJV with Hembd’s help, false friends I hadn’t noticed before. One of the reasons I push myself to work through bunches of examples like those above is that I always learn something by following the pathways of someone else’s mind. I hadn’t noticed that “experience” in Rom 5:4 was a false friend. I’m grateful to Hembd for this.

God’s voice is stronger than human foibles

And here’s a bigger lesson I learned through the many hours I somehow found in which to write this piece: it’s pretty rare that a single mistranslation can overcome the Scripture’s other teaching on a given subject. The most (in)famous biblical mistranslation in history is probably the one that Luther critiques in the first of his 95 Theses: poenitentiam agite. He explained in a letter,

I became so bold as to believe that they were wrong who attributed so much to penitential works that they left us hardly anything of poenitentia, except some trivial satisfactions on the one hand and a most laborious confession on the other. It is evident that they were misled by the Latin term, because the expression poenitentiam agere suggests more an action than a change in disposition; and in no way does this do justice to the Greek metanoein.2

And yet could even this mistranslation overcome the stories of repentance we see in the Bible? Manasseh, the Prodigal Son, the apostle Paul—can you read any of those stories and come away thinking that the really important thing in repentance is to perform a list of actions and say a number of chants prescribed to you by a priestly confessor? The mistranslation created some static, apparently—some misdirection. But God’s voice is powerful enough to speak over that static, and his providence is capable of bringing people in the right direction. A lot of hands are wrung over English Bible translation (FIRST WORLD PROBLEMS), and some of the worry is justified: there are real theological liberals out there and real cults. But the likelihood that people today in this literate age will be actively misled by a mistranslation is, in my mind, rather low. It’s been 40 years since modern translations started superseding the KJV, and I’m not aware of a single person who has doubted the deity of Christ because of reading one.

Sometimes I find myself wondering what kind of reader could ever come to the horribly theologically wrong-headed conclusions Hembd and other KJV defenders fear. It would have to be at the same time a very subtle and perceptive reader who can notice tiny loopholes through which to pull false doctrine and a reader who couldn’t hit the broadside of a library from ten feet away—someone who misses the most obvious points about the whole of Scripture because he is hurrying so fast on the broad road to destruction. Such people, it seems to me, will find ways to misunderstand even the most accurate translation. Again, we had plenty of heretics in the English-speaking world during the centuries in which the KJV was effectively our sole Bible. Historians agree that Joseph Smith was not reading an early-release version of the NIV.

This doesn’t mean we should be lackadaisical in our Bible translation work. It means we should trust God, do our best to train and work well, and seek constructive criticism from qualified people who can devote real time and study to the questions that come up. That’s what a committee is for.

The KJV committee specifically said their work was not perfect. Ours isn’t either, and neither is our knowledge of Hebrew and Greek. All this means we can expect toss-ups—and the need for alternative renderings in the margin, or perhaps even in a separate translation. Far from confusing me, I have found the use of multiple English Bible translations to aid my understanding of the Bible over and over again for two decades. By checking multiple translations, I’m likely to overcome whatever minor human foibles did find their way into a given English Bible version.

The danger of insufficient sampling

Hembd gave sixteen examples of alleged translational errors in the NKJV. I don’t count nos. 6 and 9, because they are textual matters; I don’t count nos. 14 and 15, because they are a complaint about contemporary English and not about the NKJV. (And I’m tempted not to include nos. 16 and 18, because they are complaints about the NKJV’s overall capitalization policy more so than about specific renderings. But I’ll keep these to be generous!)

I’d now like to ask a question I’ve asked before: how many examples from a Bible translation are needed in order to avoid the charge of insufficient sampling?

Is sixteen a big enough number to justify Hembd’s conclusion? Here is that conclusion:

The New King James…demonstrates itself to be a new translation and sadly an inferior one at that. The doctrinal truth and power of the originals, we submit, does not come through this translation.

I’m going to have to say that Hembd provides a classic example of the logical fallacy of insufficient sampling.

Every Bible translation, as I said earlier, is a collection of hundreds of thousands of choices. It takes a lot of careful homework to evaluate a sufficient number of these choices to form a reliable general impression. It would try the patience of even the most dedicated scholar (or inmate in solitary confinement) to talk through even a hundred examples, let alone a thousand. It’s likely that most articles which attempt to do what Hembd has attempted will be similarly limited in the number of passages they can discuss. And that means the author will have to work extra hard to show that his judgment is trustworthy in the few cases he does select for discussion.

But I’ve advanced reasons above to question Hembd’s judgment. Fundamentally, I don’t think you can gauge the quality of 800,000 choices by making rather disputable criticisms of sixteen of them.

Humble and charitable listening

I’ve often shaken my head while reading ardent defenses of the KJV in which the authors feel they must attack modern translations. The contemporary Bible translators they’re attacking are, by any reasonable (Phil 4:5) measure, more accomplished and educated and published than they are. This doesn’t mean the KJV defenders are wrong and the evangelical biblical studies PhDs are right. Education does not equal truth. Lengthy C.V.’s don’t equal personal holiness. But it does mean that KJV polemicists ought to tread a little more, well, humbly.

Once a few years ago I ran across an argument that D.A. Carson made in defense of glossolalia that I thought was uncharacteristically weak, to the point of—and this is the only time I’ve ever felt this about anything said or written by this great man—laughable. But he is so far above my level in every field I care about, and I am so grateful for countless insights he’s offered me, that I would be very circumspect and deferential if I ever felt I needed to bring this up. I would give five disclaimers about his brilliance and gifting before uttering my criticism (um, I’m doing it now). I would work to maintain my hearer’s trust in and respect for this man. I have to go with my scripturally informed conscience against his in this one case, but it’s easy to do this with a humble attitude. He has more than earned my respect and trust through dozens of articles and sermons and lectures and books that have benefited my mind and my soul greatly.

If my brothers in Christ who prefer the KJV have serious complaints about modern translations, they must enter the scholarly arena and show that they belong there by using its first tool: hard, charitable listening. They must present their opponents’ best case and not erect a series of straw men constructed on already lit funeral pyres.

Hembd’s work reminds me of the 18th century grammarian who collected dozens of examples from famous writers of what he alleged to be terrible violations of English grammar. Only these rules were ones he made up, “rules” that no else acknowledged. Lexicographer Sidney Landau commented of this poor pedant,

From any rational view he would seem to have collected a vast body of evidence to refute his own argument.

Whenever Hembd lines up against every last evangelical biblical scholar who has chosen “character” over “experience” or “Hades” over “hell,” one might be forgiven for thinking that the burden of proof is on him and not on them. At the very least, he ought to show clear and honest understanding of the reasons behind their choices before accusing them of doctrinal error. This Hembd did once in 38,000 words.

Cavils and speculations